2001-2003

YOSEMITE IN TIME

Text by Rebecca Solnit • Photographs by Mark Klett & Byron Wolfe

The idea for this project came from the writer Rebecca Solnit, who had recently finished the research for her book on the photographer Eadweard Muybridge, River of Shadows: Eadweard Mubridge and the Technological Wild West (2003). Rebecca proposed a new project to re-photograph Yosemite photographs Muybridge made in 1872. Byron Wolfe and I were just finishing the Third View DVD work, and we agreed to a three-person collaboration.

The project began by locating the sites and rephotographing Muybridge's photographs in Yosemite National Park. Fieldwork involved the three of us camping together and visiting sites mutually chosen. We soon discovered that some of Muybridge's photographs were made close to one another, and we experimented with how we might make links between two separate but related vantage points; an example is the Ghost River panorama. We also found that other photographers from different periods made photographs at or near Muybridge's vantage points, so the project soon expanded to include their images as well.

Byron and I had wanted to move beyond the now familiar methods for making rephotographs established in the RSP and used again in our Third View collaboration. The challenge in Yosemite was to integrate multiple photographs into one panorama, combining pictures made over different periods and from slightly different positions in space. The idea of combining photographs into one composite image had been made practical by the availability of digital editing tools. The photographs for this project were still made on film because digital cameras were not yet advanced enough to produce detailed images. But it was possible to make highly detailed digital prints once film scans were edited first in Photoshop. That enabled us to combine our photographs made on film with scans of historical images.

Fieldwork for the project took place over three years, usually during two one-week periods each summer. The first year we camped at a private site on the west end of the park. The next two summers we camped at Mono Lake outside the park and commuted each day to our field destinations. During these long commutes we discussed the photography and Rebecca's re-search, and we exchanged ideas about Yosemite, representation, historical facts, and photography's relationship to time, all of which helped grow and refine the project's focus.

The project book, Yosemite in Time: Ice Ages, Tree Clocks, and Ghost Rivers, was published

in 2005.

Ghost River

or Photography in Yosemite

I once heard Martin Broken Leg, a Rosebud Sioux who is an Episcopal priest, address an audience of Lutheran pastors on the subject of bridging the Native American /white culture gap. "Ghosts don't exist in some cultures," he said, adding dismissively, "They think time exists." There was nervous laughter; we knew he had us. Time is real to us in America, time is money. Ghosts are nothing, and place is nothing.

—KATHLEEN NORRIS, Dakota: A Spiritual Geography

LOOKING FOR 1872

Yosemite Valley is packed with superlative vertical spectacles— tall cascades, immense granite walls, monoliths, and spires-but quietly meandering all its seven-mile length, often shrouded in trees, is the Merced River, not the widest or longest or most anything, just the usual miracle of a river, transporting snowmelt from high country streams through the valley and down deep canyons to the San Joaquin River and eventually to the sea. The river enchanted the photographer Eadweard Muy-bridge, and water is the primary subject of more than half of the fifty-one gargantuan prints in his 1872 series titled "The Valley of the Yosemite, Sierra Nevada Mountains, and Mari-posa Grove of Mammoth Trees." He photographed the great granite behemoth of El Capitan, but made a second picture that showed not the 3,300-foot-tall wall of rock but its reflection in the still water of the Merced, where the shade from trees made the water dark and the reflection strong.

In August 2001, my collaborators Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe rephotographed the same site, but this time the reflection was in what had become a sunny stretch of river, and the result was a vague, washed-out, oddly composed picture (p.66). They could have made something that looked much more like Muybridge's image by finding a different spot with a stronger reflection, but the point was to be in the same spot to see what had changed. The exacting art of rephotography produces, among other things, random-looking photographs, since fidelity to place and fidelity to composition are different things: trees, light, water shift, and sometimes the former view is entirely obscured. To be in the same place and to be in the place where things look more or less the same are not the same thing.*

*Text by Rebecca Solnit from Yosemite in Time

Eadweard Muybridge, Valley of Yosemite, from Moonlight Rock, No. 1, 1872. Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Opening a view through the scrub oak at Moonlight Rock above the Wagon Tunnel parking lot, 2001.

Ansel Adams, Clearing Winter Storm, 1944 Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Clearing Autumn Smoke, controlled burn, 2002

Ansel Adams, Jeffery Pine, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite, National Park, ca. 1940 (left) Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, The trunk of Jeffery Pine, killed by drought, Sentinel Dome, 2002

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Eight minutes at Glacier Point, 2002

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, View from the handrail at Glacier National Point overlook, connecting views from Ansel Adams to Carleton Watkins, 2003. Left insert: Ansel Adams, c. 1935. Right inset: Carleton E. Watkins, 1861. (Watkin's photograph shows the distorting effects of his camera's movements as he focused the scene.)

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Lunar eclipse on Muybridge's Ancient Glacier, Channel, at Lake Tenaya, 1872, 2001

Carleton E. Watkins. Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove, 33 Ft. Diam., 1861. Mark Klett and Byron Wilde, Grizzly Giant from the walkway through the Mariposa Grove, 2003. (Rectangle indicates cropping of Watkin's photograph.)

Eadweard Muybridge, Yosemite Creek. Summit of Falls at Low Water. No. 44, 1872. Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Yosemite Creek at the summit of the falls, in the dry season, 2022.

Glaciers and Gods

or Science in the Sierra Nevada

…that coherence we call God…

—BARRY LOPEZ in conversation, October 2022

There were times in this project when Mark would tell me his camera was within inches of Muybridge's and times when he said that he was a lot more approximate somewhere within several feet, precise enough by anyone else's standards. He and Byron saw things that were entirely invisible or unreadable to me, not only the details of rock formations in relation to each other that let them come close to the exact spot where a photograph was taken, but the angle of light that determined what time of year and day Muybridge had been there. Once, standing by the rock in the foreground of his Bridalveil Falls photograph, though with young forest occluding everything else between us and the falls that had been visible in 1872, Mark commented: "Right time of year, but he was here half an hour earlier than us," and I pictured that artist hastening away before as just out of reach.

But once spatial distance is eliminated, the span of time can begin to be measured, and temporal distance is often immeasurably vast. Visible in the landscape are changes in trees, rocks, waterways, for no landscape stays the same even for an hour, let alone a century: But the peon who stood there in the same spot ale stood in a different world. When Muybridge worked in Yosemite, a great roadless unindustrialized expanse stretched away in all direction from a place that could be reached only on horseback or on foot, a place still being mapped, a place whose indigenous inhabitants were still unobtrusively gathering acorns and living in cedarbark structures in the valley. Muybridge, with his hobnail boots and mule caravan of photographic equipment, was in a very remote place indeed, as I realized one day when Byron took a GPS reading of our site, for the California skies in 1872 sell belonged to binds, clouds, and the beyond, while ours are cluttered with signals, satellites, airplanes, smogs, and anxieties.

Yet looking back at them from the early twenty-first century, the Victorians who came tramping through Yosemite seem closer to us than many of the figurer of the mid twentieth century because the urgent intensity with which they scrutinized the landscape is not so far from our own. For them the crisis of meaning came about with the collapse of an old order, in which humanity was distinct from the rest of the species and at the center of a world presided over by an actively involved God. For at least the environmentally inclined among us, the alarming questions now are about our own rise to near-divine status. We have changed the weather, wiped out species, modified the genetic code, paved over vast expanses of landscape. For the Victorians, the past was a destabilized zone that threatened to radically redefine their sense of self and place in the world. The Darwinian revolution frightened people by reducing their scale. Now we are giants. Our doubts are located in a nebulous future whose crises can also be found in Yosemite. It is as though our predecessors were looking down into a tremendous chasm opening at their feet. We look up at a bricked-over sky against which we may smash our heads.*

*Text by Rebecca Solnit from Yosemite in Time

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Last picture of the project, August 15, 2003: all that was left of a lens that fell down an avalanche chute during an attempt to rephotograph Agassiz Rock.

Eadweard Muybridge, Tutocanula, Valley of the Yosemite. The Great Cheif "El Capitan."3500 Feet High.No. 9, 1872 Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, El Capitan from bank of the Merced River, Yosemite Valley, 2002.

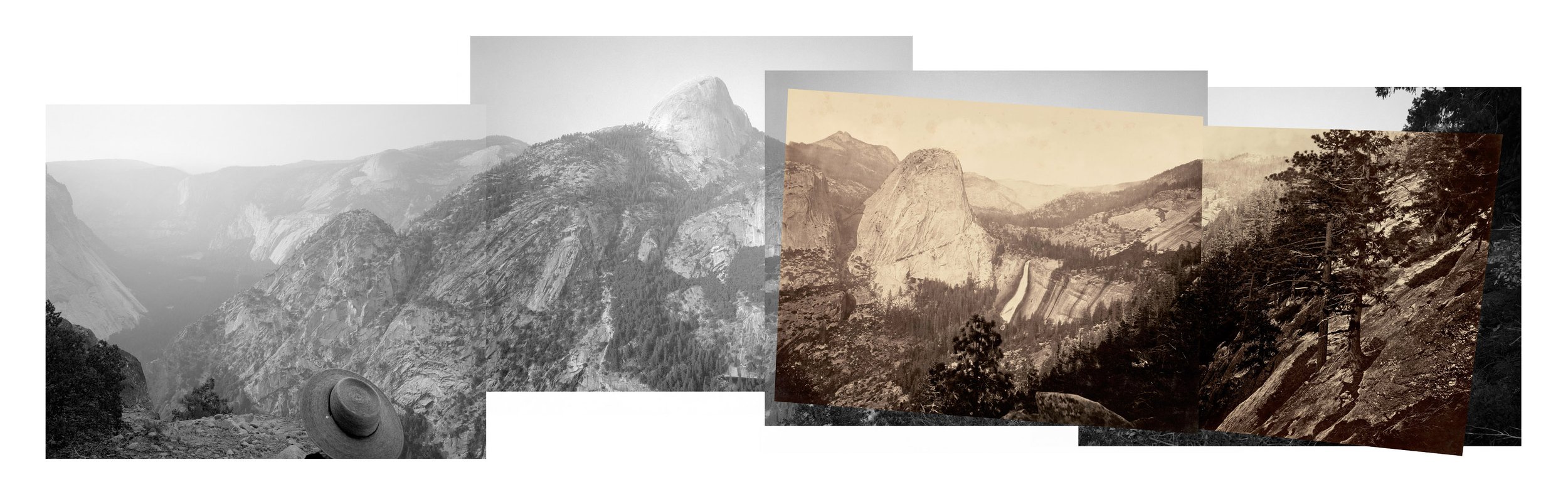

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. Panorama of a ghost river, made over 100 meters and two days beginning and ending with Muybridge's mammoth plates No. 11 and No. 12, 2001.

Four Views of Cathedral Rocks. Top Left: Carleton E. Watkins, 1861. Top Right: Eadweard Muybridge, 172. Bottom left: Ansel Adams, c. 1944. Bottom right: Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, 2022. (The last view is made from Ansel Adam's camera position, using lighting consistent with versions by Eadweard Muybridge and Carleton Watkins.)

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Four views from "Panorama Rock," an obscure outcrop off the Panorama Cliff Trail: two rephotographs, a speculation on Muybrige's missing plate No. 39, and another photograph added to the left,2002.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Panorama from Sentinel Dome connecting three views by Carleton Watkins, 2003. Left inset: From the Sentinel Dome, Down the Valley, Yosemite, 1865-66. Center insert: Yosemite Falls from Sentinel Dome, 1865-66. Right insert: The Domes, from the Sentinel Dome, 1865-66.

Mark Klett, Panorama showing Carleton Watkin's camera position for Yosemite Falls and the Merced River, 2003.

Back at the Lake

with Two Names

or the Politics of the Place

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth, but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity…

—WORDSWORTH, “Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey”

The Way There

On Monday, July 30, 2001, we located the site where Eadweard Muybridge had, 129 years before, made his photograph Ancient Glacier Channel at Lake Tenaya, the first we found and rephotographed (p. 122). Of all the sites of his photographs we explored, this one seemed to show the least change. The same crack ran down the glacial polish, hardly enlarged since his time, and not only the same boulders but some of the same smaller stones were in the same place, though the trees had changed. They were newer in the twenty-first century than they had been in the nineteenth. Where one old lodgepole pine had stood in a small patch of soil, a young one with a thinner, darker trunk grew, and a dense grove of young pines

The glaciers that made this place many thousands of years ago made it literally, scooping out the basin of the small lake, rounding the peaks into domes, grinding the long sheets of granite into the finest glacial polish anywhere on earth. The shape and the surface of the Lake Tenaya region come from glaciers. But its meaning comes from things that aren't so solid or so easy to see. On or about June 5, 1851, a contingent of the Mariposa Battalion of volunteer soldiers arrived at this lake. This first white incursion into the area had begun earlier that spring, when the battalion led by James Savage had marched in to remove or annihilate the longtime inhabitants of Yosemite, who were interfering with the economic development of the region. Among the contingent of prisoners and captors who arrived at the lake that early June of 1851 was an old man, sometimes secured by a rope around his waist:

Tenaya, the leader of inhabitants of Yosemite Valley. Sometimes holding the other end of the rope was a young man soaked in the romantic landscape traditions of Europe and the East, Lafayette Bunnell. Bunnell's is the main account of what transpired there that bloody spring, and his book is a peculiar mix of rhapsodic responses to the place and indifferent and scornful ones to the landscape's inhabitants. It is in his responses to scenery, not people, that he attempts to demonstrate his humanity and his civility.*

*Text by Rebecca Solnit from Yosemite in Time

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Four views from four times and one shoreline, Lake Tenaya, 2002; left to right; Eadweard Muybridge, 1872; Ansel Adams, ca. 1942; Edward Weston, 1937; back panels: Swatting high-country mosquitos, 2002

Ansel Adams, Rock Veins, Tenaya Lake, Yosemite National Park, ca. 1935 Mark Klettt and Byron Wolfe, Rock Veins with stones used for framing, and water to wet rock and increase contrast, 2003.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Above Lake Tenaya, connecting views from Edward Weston to Eadweard Muybridge, 2002; left: Edward Weston, Juniper, 1936; right: Eadweard Mubridge, Ancient Glacier Channel, at Lake Tenaya, Mammoth Plate No. 47, 1872

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Above Lake Tenaya, connecting two 1940s by Edward Weston, 2003.

Related:

Yosemite in Time, Ice Ages, Tree Clocks, Ghost Rivers, with Rebecca Solnit and Byron Wolfe

Trinity University Press, San Antonio, 2005 and 2008