2007-2012

Reconstructing the View

In the spring of 2007 Byron Wolfe and I considered the possibility of starting a new project.

I suggested we take a trip to the Grand Canyon. It was conveniently located for us both geo-graphically, and there was a huge number of historical images of the canyon that we could mine online. The Yosemite project had expanded the methods we'd been using to rephotograph historical images, and there had been several compelling changes in technology since the end of that project that we wanted to explore. We were interested in taking up where the last project had ended, and the national parks seemed to offer opportunities as places of high image density. Plus, the photographs made in the Grand Canyon were among the most iconic of American land-scapes.

We realized after the first week of fieldwork that the possibilities for making new work at the Grand Canyon were even greater than we had expected. Our tools and research methods had changed in the four years since the Yosemite project had ended. We were using a medium-format digital sensor on a type of digital view camera that could rival the detail of traditional film-based large-format photography. And the instant feedback we could receive by downloading digital images to a laptop offered us greater options while we were still on site, similar to the way the Polaroid film had given us on-site feedback in the past. We even had a portable printer that allowed us to print out photographs in the field. It was a totally different kind of digital photography than what we first employed for Third View ten years earlier. The digital camera we used at the start of the Grand Canyon project had almost twenty times greater resolution than my first digital camera. By the end of three years working at the Grand Canyon, we had yet another digital camera, and the detailed resolution we could capture doubled again.

There was no simple formula for the methods we used at the Grand Canyon, but the rule of thumb was to attempt new ways of working as often as possible. The digital tools available to us seemed to finally match our vision. Technical changes were still happening quickly, and when new devices were introduced such as the Apple iPad, we thought of how we might use them to visualize the canyon in a new way.

Our research into historical images was often done during field trips, after visiting the space first, by searching the web in a hotel lobby or cafeteria on our laptop computers or using our phones. Since the equipment was more portable than in the past we could often visualize the way a piece might come together while we were still on site.

We visited the canyon twice a summer, usually in May or June and again in August, spending a week on each trip. We would travel to both the north and south parts of the canyon, and our work was mostly confined to the rims where almost all of the historical photographs were made.

At first, all views of the canyon looked the same to me. But as we grew to understand the canyon's geography, our knowledge of the features and the ways photographs recorded them improved, and that allowed us to understand how photographs have represented or failed to represent scenes of incredible depth and how they were flattened into two-dimensional planes.

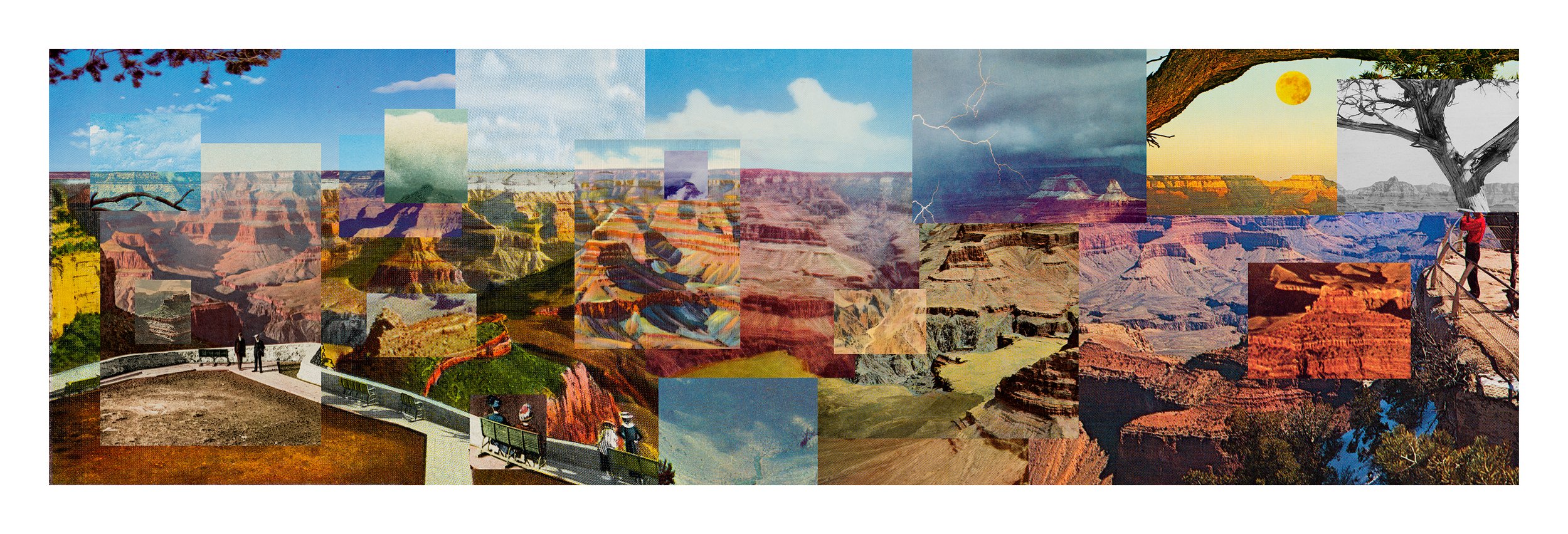

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Reconstructing the view from the El Tovar to Yavapai Point using nineteen postcards, 2008

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Rock formations on the road to Lee's Ferry, AZ, 2008; left inset: William Bell, Plateau North of the Colorado River near the Paria, 1872; right inset: William Bell, Headlands North of the Colorado River, 1872

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, One hundred and five years of photographs and seventeen million years of landscapes; Panorama from Yavapai Point on the Grand Canyon connecting photographs by Ansel Adams, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and the Detroit Publishing Company, 2007; left, two views: Ansel Adams, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1941; middle: Alvin Langdon Coburn,Bright Angel Canyon, ca. 1911; right: Detroit Publishing Company, The Grand Canyon of Arizona Across from O'Neil Point, 1902

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, 2010. Arthur Wesley Dow on the edge at Hopi Point, photographed by Alvin Langdon Coburn in 1911. Right: Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1911. Arthur Wesley Down Grand Canyon.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe,Stereo view of Isis Temple,2010; right: Ansel Adams, View of Rock Formations, Grand Canyon National Park, 1943

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Confirming the details of the moment across the geologic horizon of Marble Canyon. Views from a military spotting scope on the Platform where William Holmes drew the eastern edge of the Kaibab in 1882, 2008; background: William Henry Holmes, Views from the Marble Cañon Platform from the Eastern Brink of the Kaibab, 1882, lithograph, sheet XIX, from Clarence Dutton,Atlas to Accompany the Monograph on the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Panorama of Hopi Point based on the horizon line from west to east, 2008; insets, left to right: Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, South rim edge looking west at sunrise, 2007; Mark Klett, Picnic on the edge of the rim, 1983; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Storm above south rim, 2007; unknown, postcard, n.d.; unknown, souvenir album, n.d.; unknown, colored postcard, n.d.; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, North rim at midday, 2007; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe,North rim in clouds, 2007; unknown, postcard, n.d.; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Storm clouds 1, 2007; unknown, souvenir album, 2007; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Storm clouds 2, 2007; unknown, colored postcard, n.d.; Ansel Adams, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1941; Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Edge of south rim looking east, 2007

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Panorama from Hopi Point on the Grand Canyon, made over two days extending the view of Ansel Adams, 2007; right: Ansel Adams, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1941

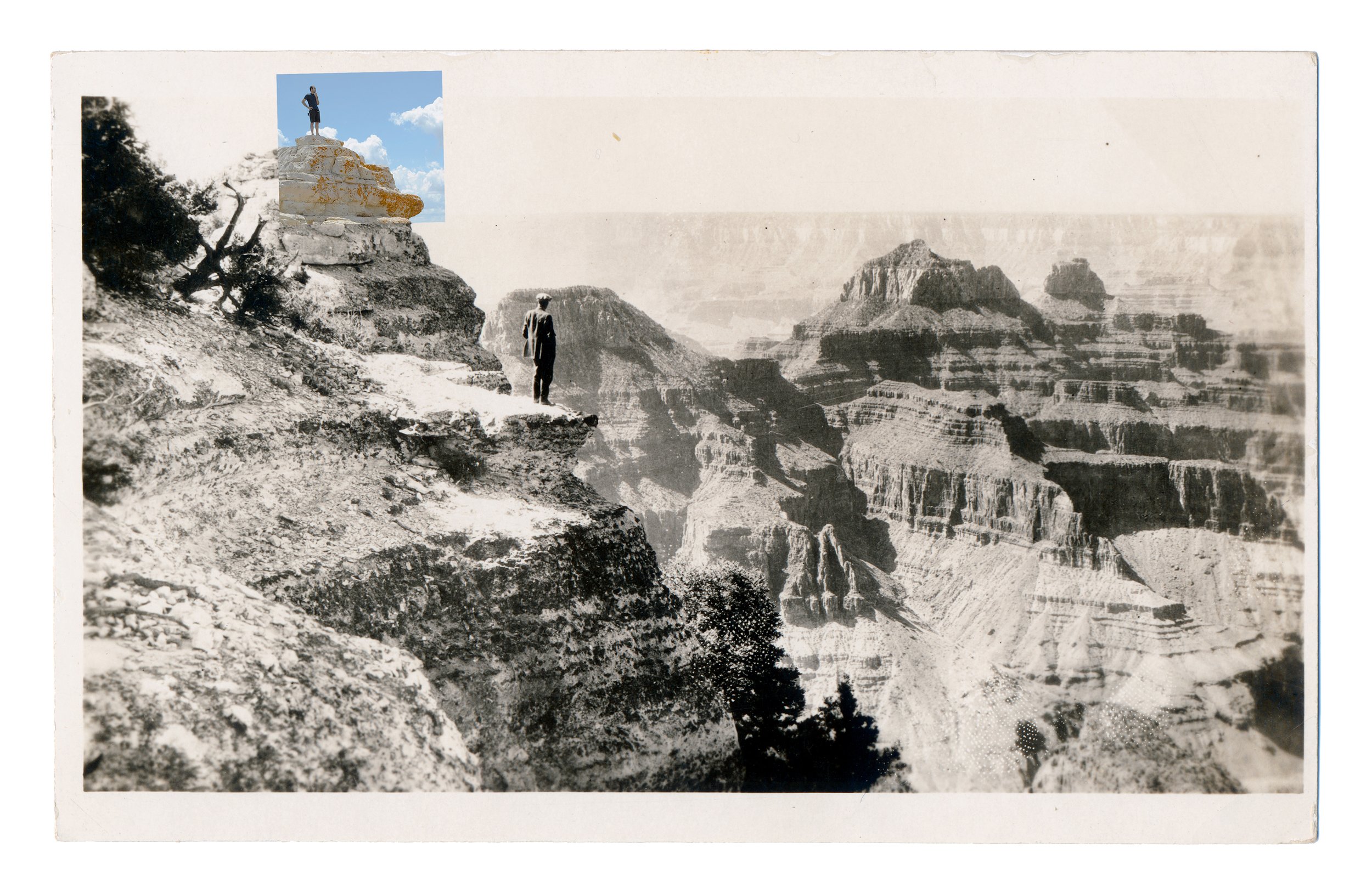

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Grand Canyon, 2010 (altered postcard)

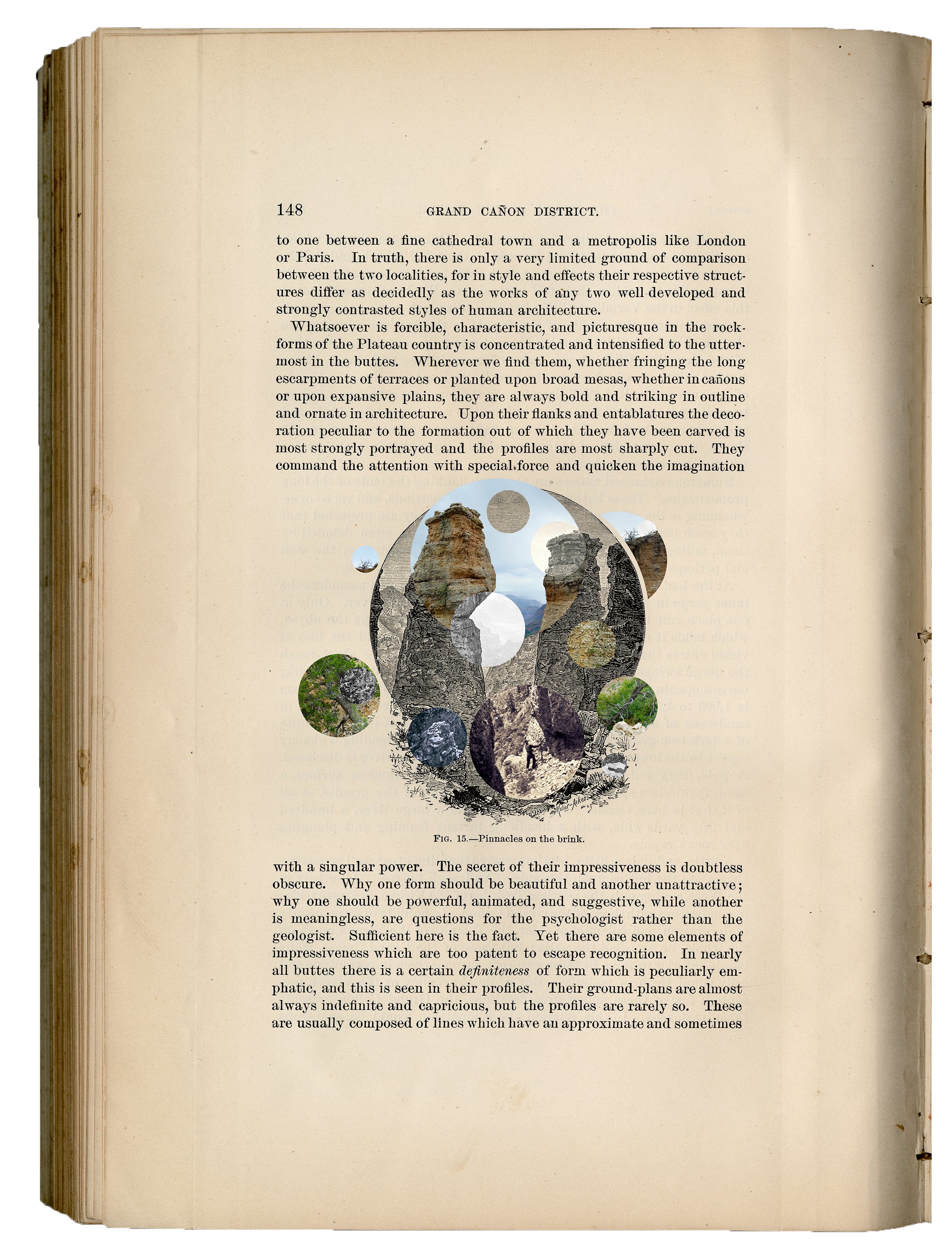

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Pinnacles on the Brink, 2010; book page and engraving: Capt. C.E. Dutton, Second Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey to the Secretary of the Interior, 1880-81; Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District; inset: portion of stereo photograph, J.K. Hillers, Grand Canyon, Mauv Canyon, Colorado River, 1873 and Mark Klett, Hoodoo Rocks near Mauve Saddle, 8/12/09

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, People on the edge, 2008; unknown, stereo views, n.d. Select the Image to see a Larger Size

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Sixty-six years after Edward Weston's Storm, Arizona from the Marble Canyon Trading Post, 2007; left: Edward Weston, Storm, Arizona, 1941

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, View from the south rim of the Grand Canyon with Thomas Moran and California Condor, number 302, 2007; right: unknown, ca. 1907; Thomas Moran, America's greatest scenic artist sketching at Bright Angel Cove, Arizona, half of stereo view.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Details from the view at Point Sublime on the north rim of the Grand Canyon, based on the panoramic drawing by William Holmes in 1882, 2007; William Henry Holmes, Panorama of Point Sublime, 1882, sheets XV, XVI, XVII, from Clarence Dutton, Atlas to Accompany the Monograph on the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Site of a dangerous leap, now overgrown, 2008; inset: colored postcard, n.d.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, 2010. Figures at Bright Angel Point, north rim, Grand Canyon. Altered postcard.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, 2010. All that matched the view of Thomas Moran’s sketch “Grand Cañon of the Colorado” with pieces from Dutton Point, Muav Saddle, and Swamp Point. Back: Thomas Moran, 1873. Grand Cañon of the Colorado. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, 2010. Man contemplating the base of Vermillion Cliffs one hundred and thirty-eight years earlier. Inset: William Bell, 1872. Near Jacob’s Pool, Northern Arizona. Partial selection form stereo card. National Archives.

Related:

Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett

& Byron Wolfe.

University Of California Press, Berkeley, 2012